ChinAI #217: Year 5 of ChinAI (China's Diffusion Deficit in Scientific and Technological Power)

Greetings from a world where…

ChinAI is now five years old, which means it should be able to draw more realistic images, stand on one foot for at least 10 seconds, and write its own name — though, we’re still working on that last one (there’s a weird capital letter in the middle)

…As always, the searchable archive of all past issues is here. Please please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay support access for all AND compensation for awesome ChinAI contributors).

Reflection on Five Years of ChinAI: China's Diffusion Deficit in Scientific and Technological Power

Earlier this month, I published my first solo-authored article in Review of International Political Economy: “The diffusion deficit in scientific and technological power: re-assessing China’s rise.”

As much of my writing tends to do (if you’ve been reading ChinAI for five years, you should be used to this), this article begins with a complaint. Assessments of national scientific and technological capabilities are unduly obsessed with innovation capacity, or which state will be the first to pioneer new breakthroughs. Instead, I argue that more attention should go toward diffusion capacity: a state’s ability to spread and adopt innovations, after their initial introduction, across productive processes.

When a substantial gap exists between a state’s innovation capacity and diffusion capacity, conventional measures of its scientific and technological prowess (e.g., indicators based on patents, R&D spending, high-end talent) will be misleading. There are two types of gaps. First, a diffusion surplus: when a rising power has a strong diffusion capacity but weak innovation capacity, it is more likely to sustain its rise than innovation-centric assessments portray. In the article, I illustrate this with a case study of the U.S. in the late 19th century. Back then, scholarly and media reports bemoaned the fact that the U.S. lacked centers of excellence comparable to Germany, Britain, and France; however, they underrated the U.S.’s leadership in adopting new advances at scale.

For China, the second type of gap is most relevant. In cases of a diffusion deficit, when a rising power possesses a strong innovation capacity but weak diffusion capacity, it is less likely to sustain its rise than innovation-centric assessments depict. The relevant historical precedent is the Soviet Union in the early postwar period. In this case, the Soviet Union paced the world in R&D spending, top scientists (as measured by STEM PhD graduates), and other indicators of innovation capacity. Yet, it lagged in diffusion capacity. I cite one assessment from 1969 on this point: “In no major branch of industry is the average level of Soviet technology in use on a par with that in the United States or Western Europe.”

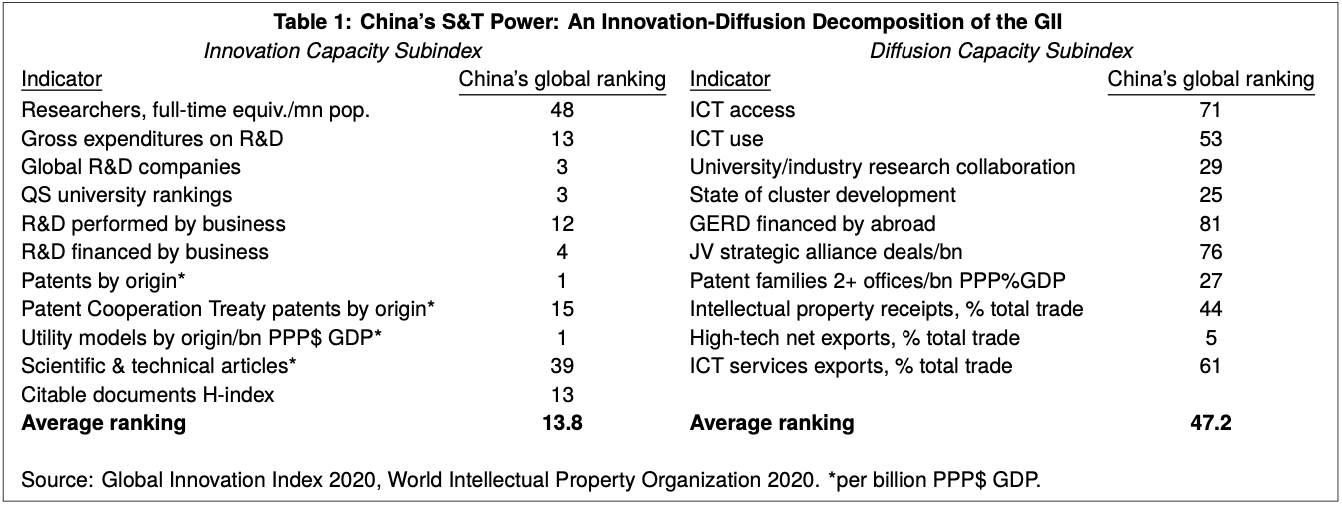

In the last part of the article, I contend that China faces a diffusion deficit. I support this with a decomposition analysis of two indexes that rank countries on a wide range of national scientific and technological indicators: the Global Innovation Index (GII) and the Global Competitiveness Index. Essentially, I sorted these indicators by their association with diffusion capacity or innovation capacity. R&D expenditures of a country’s top three firms? Innovation capacity. Adoption rates of various information technologies across businesses? Diffusion capacity. Table 1 shows how China’s average global ranking on diffusion capacity significantly trails behind its innovation capacity.

My findings suggest that conventional (read: innovation-centric) assessments misleadingly inflate China’s scientific and technological capabilities. For instance, in President Biden’s first remarks to Congress, he focused on the need to dominate breakthroughs in the technologies of the future. According to Biden, the U.S. is “falling behind in that competition … China and other countries are closing in fast.” His speech reflected two common themes in discussion about national S&T capabilities: 1) an obsession with innovation capacity; 2) a belief that China was poised to overtake or has already surpassed the U.S. in science and technology. Essentially, what this article does is show how the first theme influences the second, and in the process, challenge both.

I welcome rebuttals and debates on these points. Last month, I had the opportunity to testify on China’s diffusion deficit to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a Congressional body that monitors U.S.-China economic and security relations. There was some good back-and-forth with the commissioners on the paper’s findings and methodology. This C-SPAN video includes some starred timestamps on key moments.

One reason I wanted to highlight this article for this ChinAI milestone is because it builds on themes that this newsletter’s translations have been exploring over the course of five years. Take, as an example, this passage from the article on China’s low rates of digitalization:

While China has achieved a few noteworthy successes in ICT diffusion in consumer-facing applications – such as the spread of mobile payments and e-commerce – Chinese businesses have been slow to embrace digital transformation. China lags behind the U.S. in penetration rates of many digital technologies across industrial applications, including digital factories, industrial robots, smart sensors, key industrial software, and cloud computing (Alibaba Research Institute, 2019; Synced, 2020; Techxcope, 2020).

The three references all come from ChinAI translations: Alibaba Research Institute’s report on China’s digital economy (ChinAI #90); a Synced report on digitization in small, medium, and micro businesses (ChinAI #119); and a Techxcope article on Germany’s success with technology transfer centers that spur diffusion (ChinAI #121). Interesting ideas come from original wellsprings. If I only read English-language news, I would not have developed this diffusion deficit argument.

Indeed, this diffusion deficit article reflects what I try to prioritize with ChinAI coverage. Everyone is focused on which lab will produce China’s version of ChatGPT; I’m more interested in Chinese organizations that are trying to “make large models cost-effective to enable use by small businesses, students, and governments” (ChinAI #199: China’s Hugging Face). There’s a lot of coverage on which Chinese facial recognition company is the world’s most valuable AI start-up; more newsworthy to me is how Chinese companies are trying to get better at making knives by adapting computer vision for detecting defects early on in production lines (ChinAI #58: Making Knives Better & Landscape of China's Intelligent Manufacturing).

Cheers to another year. Thanks to everyone who supports ChinAI, whether that’s via paying for a subscription, forwarding issues, or helping out with translations. If you could take a few minutes to diffuse the word about “The Diffusion Deficit in Scientific and Technological Power,” that would be much appreciated!

Thank you for reading and engaging.

These are Jeff Ding's (sometimes) weekly translations of Chinese-language musings on AI and related topics. Jeff is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University.

Check out the archive of all past issues here & please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay for a subscription will support access for all).

Any suggestions or feedback? Let me know at chinainewsletter@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jjding99