Greetings from a world where…

classes are somehow starting this week

…As always, the searchable archive of all past issues is here. Please please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay support access for all AND compensation for awesome ChinAI contributors).

Feature Translation: A cruel reality for Chinese AI chip companies

Context: Who can surpass Cambricon [寒武纪] (China’s AI chip giant)? That’s the title of Leiphone’s latest series of articles on China’s AI chip industry. This week’s feature translation (link to original Chinese) examines the turmoil in this industry, especially as it relates to pursuing a public listing. Two other pieces of context: 1) Shanghai Enflame and Shanghai Biren are two AI chips startups who have recently began seeking advice to list on Shanghai’s STAR exchange; 2) in this article, AI chips refer to chips for training large models, not chips for specific AI applications (e.g., the ones that Horizon Robotics makes for autonomous vehicles).

Key Takeaways: Going public, seemingly a natural step forward, can actually suggest remarkably different destinies for these AI chip companies. Junyuan and Haotian’s stories represent these two sides of the coin.

After school, Haotian joined the product department of a U.S. chip company. Feeling stuck in a conflict between his Chinese supervisor and American supervisor, he left to join a Chinese AI chip startup. Even though he had received stock options worth 8 million RMB in his startup, he didn’t believe in the competitiveness of the products (“the chips sold were not actually used”).

Haotian resigned before the company filed an IPO: “Even if the company can successfully go public in 2025, based on the stock options I have received, it seems that I can cash in nearly 8 million in five or six years, but…it is not as much as it seems. If the company's sales do not improve during this period, the salary will not increase and the bonus is not satisfactory, so the options are not my motivation to continue working.”

Senior engineer Junyuan has a different mindset. He put his entire 2023 year-end bonus into company options.

He joined a Chinese AI chip startup in 2018. After the company’s 2nd-generation chip successfully launched, management started talking about a public listing.

He expressed, “After the listing, my life should be worry-free.” Part of this belief is due to the firm’s revenue growth, but part of it is due to his age: “I am already in my forties. Even if there is a good opportunity to go to a new startup and wait for the company to go public, I can't wait that long. I can only concentrate on writing code for 10 years at most.”

The prospect of listing on a stock exchange creates pressures that can lead to unsustainable practices. Salesperson Wei Li describes China’s AI chip industry as “trying to build a towering building without being allowed to lay the foundation.”

“A company that is going to go public has exchanged 100 million RMB for 40 to 50 million RMB in revenue by ‘passing money from one hand to the other’,” said Wei Li.

Jianguo Wang, who works in the marketing department of an AI chip company, shares another story, “Some companies really don't care about the lives of their peers. For the projects of the intelligent computing center, the price of one batch of computing power in the industry is generally about 700,000 to 800,000 RMB, but some companies preparing to go public sell one batch of computing power for 200,000 RMB, which is almost impossible for chip companies to make money.”

Criticizing these AI chip companies for trying to list without a strong basis, experienced investor Yunchuan makes an interesting comparison: “This is just like Cambricon, whose revenue in the first half of 2024 was less than 65 million (RMB), but its market value was as high as 300 billion (RMB). This set a bad demonstration effect.”

What comes next?

The U.S.’s latest update to chip controls, which now ban the sale of advanced high bandwidth memory chips to China (used in Huawei’s Ascend AI processors), will play a role. Citing bottlenecks in manufacturing, chip designer Mu Ze doesn’t have much hope, “After seeing the latest US ban, I fell into confusion. I don't know how the Chinese AI chip industry will develop in the future.”

Others are more optimistic. Junyuan states, “This time, we can see more clearly that the United States is targeting the entire domestic chip industry rather than a certain company. It can make more people who previously rushed to grab Nvidia chips realize that no matter how good Nvidia's products are, they may not be able to buy them in the future. This is good for the Chinese chip industry in the long run.”

*All names in the article are pseudonyms.

FULL TRANSLATION: Holding 8 million stock options, resigning before listing, AI chip people have no other choices

ChinAI Links (Four to Forward)

Should-listen: Machine Failing — The Linkage Between Software Development and Military Accidents

I enjoyed chatting with Rick Landgraf on Texas National Security Review’s Horns of a Dilemma podcast about my latest article: Machine Failing: How Systems Acquisition and Software Development Flaws Contribute to Military Accidents. Here’s the article’s closing pitch:

Indeed, this article puts forward that lessons from the development of automation software in older military systems can directly apply to managing emerging technology risks. Revisiting near–nuclear confrontations in the Cold War, a 2022 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists essay warned, “Today, artificial intelligence, and other new technologies, if thoughtlessly deployed could increase the risks of accidents and miscalculation even further.” In these discussions, both scholars and policymakers often gravitate toward “novel” risks, such as those linked to increased speed of decision-making. To be sure, there are many ways that AI systems today differ from the software of old. And, certainly, investigating those unique features will uncover useful insights into understanding how AI will affect military accidents. At the same time, there is much to be learned from historical cases of software-intensive military systems. After all, new technologies cannot so easily escape deep-rooted problems.

Should-read: AI and the future of workforce training

By Matthias Oschinski, Ali Crawford, and Maggie Wu, this CSET report analyzes not just alternative pathways to AI upskilling but also how AI-enabled tools will help workers prepare for these transitions. The report gathers insights from two virtual roundtable discussions with 15 experts,

Should-read: DeepSeek v3: The Six Million Dollar Model

I learned a lot from Zvi Mowshowitz’s breakdown of DeepSeek v3’s significance. The details about the model’s performance on private benchmarks was especially enlightening.

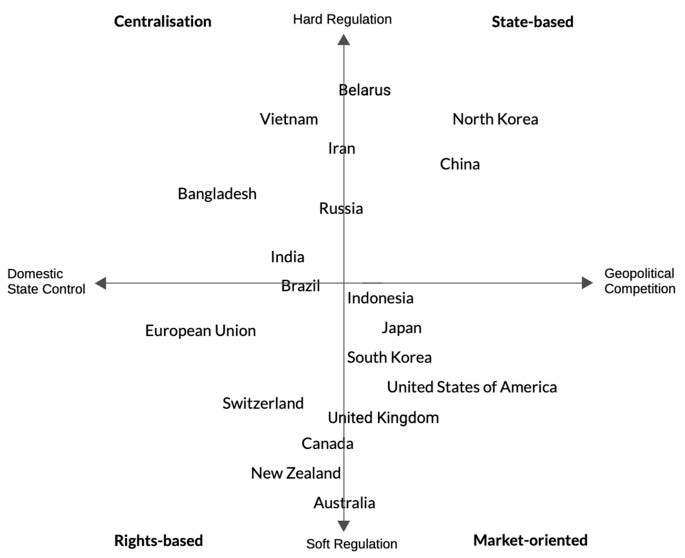

Should-read: Digital Sovereignty: A Descriptive Analysis and a Critical Evaluation of Existing Models

In Digital Society, Samuele Fratini, Emmie Hine, and others map out four different models of digital sovereignty. Their typologies (image below) raise interesting questions; for me, the horizontal axis is confusing: Isn’t China’s digital sovereignty push also about ensuring state control over digital infrastructure?

Thank you for reading and engaging.

These are Jeff Ding's (sometimes) weekly translations of Chinese-language musings on AI and related topics. Jeff is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University.

Check out the archive of all past issues here & please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay for a subscription will support access for all).

Also! Listen to narrations of the ChinAI Newsletter in podcast format here.