ChinAI #66: Autumn Chrysanthemums on the Bridge

AI Poet "Yuefu," from Huawei Noah's Ark Lab, generates various forms of Classical Chinese poetry

Welcome to the ChinAI Newsletter!

These are Jeff Ding's (sometimes) weekly translations of Chinese-language musings on AI and related topics. Jeff is a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, PhD candidate in International Relations, Researcher at GovAI/Future of Humanity Institute, and Research Fellow at the Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

Check out the archive of all past issues here and please please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay for a subscription will support access for all AND compensation for awesome ChinAI contributors like Ru-Ping from this week). We’re at 64 subscribers — the (very arbitrary) goal is to get to 100 by the end of September.

Feature Translation: Huawei launches AI poet "Yuefu"

Right at the start, let’s get a quick disclaimer out of the way: Yes, this development has “grand-strategic” implications, such as for: A) the rate of cross-border technological diffusion for fundamental models like GPT; B) assessment of the strength of Huawei’s “Noah’s Ark” a sub-lab of the 2012 lab, a turning point in Huawei’s R&D ramp-up, and perhaps foreshadowing of the rough waters coming for the company in years to come.

But at least for this one week, we’re just going to leave it at that. We’re going to enjoy reading some Classical Chinese poetry and allow ourselves to actually marvel at what this AI poet can create. Of course, I care about the grand-strategic/political implications of technology (it’s what I research all day), but at the same time I can’t help but feel that we’ve lost our sense of wonder about the beautiful things that AI can sometimes help bring about. Reading some of these poems by the AI poet/translations by Ru-Ping brought me a sense of wonder that I rarely experience (e.g. when reading Wesley Morris’s movie reviews). I hope it does the same for you.

CONTEXT: Back in June 2019, Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab published a paper on arxiv claiming to be the first to employ OpenAI’s GPT (a pre-trained natural language model) to develop a poetry generation system. Good discussion with Miles and Jack from OpenAI in this thread below, including some clarifications that others had used GPT to do poetry generation:

Regardless, this is definitely the first to employ GPT in generating classical Chinese poetry, which presents some unique challenges in terms of form, tone, rhyming, and pairing. This is another example of how Natural Language Processing (NLP) varies by the Language. It’s not enough to just get to the level where we’re talking about NLP/computer vision/predictive intelligence instead of the buzzword-catchall of AI; we also have to get to the level where we make distinctions between English NLP and Chinese NLP and NLP for low-resource languages. We’ve covered this NLP landscape in past issues.

This week’s piece, by the media platform QbitAI (which is in the ChinAI spotting guide I shared last week), first takes us through the netizen reaction to playing around with the AI poet. It ranged from the legendary poets would cry after reading this amazing piece to “It’s very neat, but I feel that most of what it is expressing is on the syntax level and not getting to the semantics level. It still likely lacks some soul.” It then gave a range of example types of poetry Huawei’s Yuefu can generate, benchmarking Yuefu against another non-GPT-based system by researchers at Tsinghua.

The Poems and their translations: Very excited to introduce some translations of Huawei Yuefu’s poetry by Ru-Ping Chen. A recent UC Berkeley graduate, her creative writing pieces have been published in The Daily Californian and her idiom translations have been published at TutorMing, a site that enables online Mandarin learning. You can follow her on Twitter @roxychen_56.

After some painstaking work translating ten or so of these poems, here are some of her reflections:

(1) I want to make it clear that my translations of these poems reflect only my personal interpretations. Specifically, I wanted to replicate the artistry typically present within poems written by renowned poets (e.g. Li Bai, Li Qingzhao).

Normally, translations should convey what the poet originally intended to get across to readers. Obviously, because I have no existing means through which I can examine what AI desires to get across to readers, I gave myself some creative freedom in translating these poems.

(2) When I translate poems written by actual poets, I usually reference texts that give in-depth analyses of how the poem is structured and the historical implications of such poems. Because these poems were generated by AI, I had no sources that I could reference.

It is important to keep this point in mind because poetry must be evaluated in the context under which it was created, a context that poems generated by AI lack. Poetry is a written representation of the human experience and unless AI evolves to a point where human feeling is possible, these AI-generated poems inherently lack the depth typically present within poems written by humans.

(3) At best, the AI referenced in this article has learned how to replicate the structure of Chinese poetry and mimic the manners in which poets assemble language to convey a degree of artistry. Scholars more qualified than I to translate these poems would likely agree that these replications bear many flaws that may not be readily perceivable by people who do not frequently read poetry.

Personally, I think meaning can be given to these poems only by humans, or else these poems become mere combinations of flowery words. Additionally, I believe these AI-generated pieces give poetry a chance to evolve because scholars/individuals no longer have to restrict their interpretations to historical/literary contexts.

Jeff jumping back in here: +1 to all of Ru-Ping’s points, and I really want to emphasize the last one — the notion that AI-generated poetry will enable poetry an opportunity to evolve, similar to the way that AlphaGo inspired more people to play Go and completely new tactics.

Can you tell the difference between poetry written by AI vs. poetry composed by legendary Tang Dynasty poets ? Midway through the piece, the author gives the readers a chance to pick out the one poem written by a Tang Dynasty poet (the other three were all written by Huawei’s AI poet):

I couldn’t tell and neither could Ru-Ping after skimming it. If any readers can guess the correct answer, tweet it at me, and I’ll personally ensure you get a special reward of somewhat arbitrary and meaningless Internet points!

Now, let’s read through three pieces of AI-generated poetry together — all translations by Ru-Ping Chen:

First up, I really like this Yuefu-composed Cang Tou Shi (Chinese version of acrostic poems) — every line’s first word or phrase can be linked up into a meaningful phrase/sentence, which is often meant to be hidden. In this case, the first words of each line form the title of the poem: 神经网络 (neural networks)

Neural Networks

Allocating divine status to a soul that has passed—it is natural,

Like the classics that preserve the virtues of ancient wisdom.

The astray scripts of the internet try earnestly to preserve their legacies,

A newfound literary wisdom that shall be passed down for centuries.

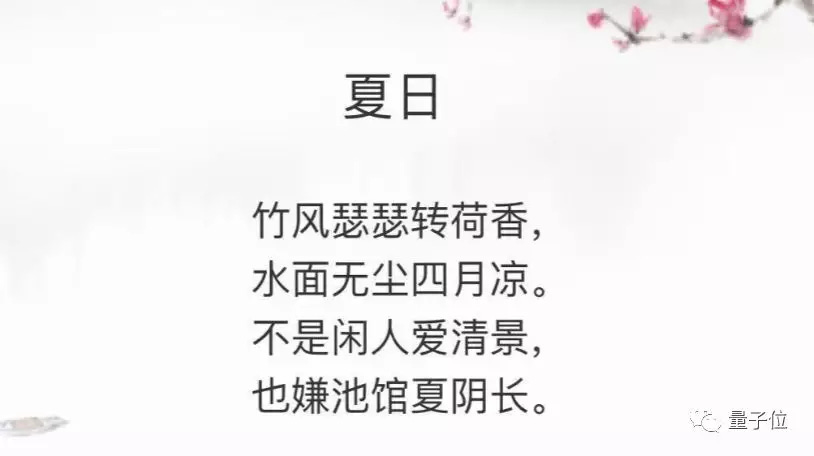

Next one is a seven-character quatrain based on the prompt of “Summer”:

Summer Days

Winds rustle the bamboo trees and spread lotus flower scents,

Oh, these April breezes—these ponds accumulate no soot.

Though the idle individual may appreciate exquisite scenery,

She laments the wearisome length of summer nights.

We’ll conclude with a lyrical poem. Manjianghong is a reference to a poem supposedly written by 岳飞, a military general who lived during the Song Dynasty. One way to interpret the poem’s meaning is of a scholarly-like figure taking a walk down memory lane and yearning for an unrequited love:

A River of Blossoms: A Stroll in the Park

An instance of rain precedes the morning sun,

Matters natural to spring few and far in number,

Inebriated, I take in the scenery of neighboring gardens.

I reminisce, I muse,

The happy-go-lucky days of my youth,

Having once tread upon greenery in seasons past.

It is early morning yet the flowers looked washed-out,

The fallen flower petals of a myriad of scents.

I care not and rely upon my drunken state with great relish,

My golden cup—a lotus flower,

I have forgotten all.

An unhinged state of being,

Restraint all but absent.

A delicate yet charming disposition,

A dainty yet fragile figure.

I care not whether that which decorates my hair has withered and fallen,

Whether my hair becomes dishevelled.

The flowers beyond the curtains adorned with swallows,

The honorable drunken literati too small to deserve honor.

I look upon a flower,

Unwilling to comprehend the poem buried in my heart,

It shall endlessly torment me.

***The full translation features other types of Classical Chinese poetry (pentasyllabic regulated verse, eight-line poem with seven characters to a line, Shuidiao Getou, and couplets, etc. Each type with its own rules regarding the number of words, rhymes, tones, and parallelism) — for more wonderful translations by Ru-Ping, see: FULL TRANSLATION: Huawei launches AI poet "Yuefu"

ChinAI Links (Four to Forward)

“Some people, and I am one, feel that Tang (618–907 CE) poetry is the finest literary art they have ever read. But does one need to learn Chinese in order to have such a view, or can classical Chinese poetry be adequately translated?” What a perfect opening paragraph in this NYRB article by Perry Link on the magic in both the art of the poetry itself as well as the art of translating it.

We’re opening up another round of the Governance of AI Fellowship, a 3-month opportunity to get up to speed with the field and hopefully do some cutting-edge research. Apply before October 13th. Start January or July 2020.

This week’s must-read piece, by Benjamin Heinzerling, argues that NLP’s “Clever Hans” moment has arrived. This is a reference to a real-life horse whose trainer claimed could perform arithmetic and other intellectual tasks, but in reality relied on involuntary cues given by its handler. In the same way, Heinzerling’s piece reminds us that as we train increasingly stronger learners, we need to pay increased attention to their ability of exploiting cues and taking unintended shortcuts.

Call for papers for University of Westminster Press volume on AI For Everyone? “This collection brings together critical debates about Artificial Intelligence (AI) to interrogate how we should understand what constitutes AI, its impact and challenges…” h/t to ChinAI reader Angela Lewis for forwarding this call.

Thank you for reading and engaging.

Shout out to everyone who is commenting on the translations - idea is to build up a community of people interested in this stuff. You can contact me at chinainewsletter@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jjding99