ChinAI #93: Year 2 of ChinAI

Reflections on Technological Trajectories and the "China-watching" Community

Welcome to the ChinAI Newsletter!

Greetings from a land where it’s been a little over two years since the start of ChinAI. We’re now at nearly 7,000 readers on the weekly email list, with 140 paying subscribers who support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model. A special thanks to everyone who contributed translations this year and also my home base at the Center for the Governance of AI at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute.

Recently, Substack announced an option for creators to add options to customize paid subscription offerings. I’ve decided to open up an additional subscription option for readers who are able/willing to subscribe at whatever amount they’d like greater than the regular plans. I’ve set the suggested amount at $150.00 for this supporter subscription plan, which lets you join the “Gambara Group” — named after Veronica Gambara (1485-1550), an Italian poet who was a great patron of writers and artists in the early Italian Renaissance. If you’re not a subscriber yet, you can either join the Gambara Group or subscribe at the regular amount. *Note: there’s currently not an easy way for existing subscribers to switch their plan to the Gambara Group tier, but Substack says it’s in the works.

As is the case with the existing subscribers, there’s no exclusive content for the Gambara Group. In the words of the managing director of membership for The Guardian, “This is not just a paywall under another name.” You are paying because you fundamentally agree with and want to support the idea of ChinAI as an open library and platform for deliberation.

When deliberating over this additional tipping option, I was thinking about Li Jin’s piece on 100 True Fans and the passion economy. Li’s insight is that platforms like Substack now enable random bloggers like me to cater to 100 True Fans (out of a much larger free audience base) who are willing to pay higher prices for exclusive content. Even though ChinAI is also supported by a small group of paying subscribers, I don’t want ChinAI to take the 100 True Fans approach but instead to keep the commons/library model. I still look to The Guardian and Wikipedia as alternative pathways — “PBS as a service” in the words of Tim Carmody at Kottke (one of the oldest blogs on the web). He writes:

The most economically powerful thing you can do is to buy something for your own enjoyment that also improves the world. This has always been the value proposition of journalism and art. It’s a nonexclusive good that’s best enjoyed nonexclusively.

Anyways. This is a prediction for 2018 and beyond. The most powerful and interesting media model will remain raising money from members who don’t just permit but insist that the product be given away for free. The value comes not just what they’re buying, but who they’re buying it from and who gets to enjoy it.

The bigger those two pools get — the bigger the membership, and the bigger the audience — the better it gets for everyone. This is why we need more tools, so more people can try to do it. PBS as a service.

I don’t want to overpromise. To be honest, this time next year, I’m not even sure if we’ll keep this going, or if we’ll have pivoted into a newsletter about China’s rap scene (an article on the history of Xinjiang hip hop has been sitting in my on-deck circle for translations for a while now), so if you’re looking for a long-term investment, I’d suggest real estate (that’s not real advice — I had to google “good long-term investments” to write this sentence). But if you’re up for deep dives into bureaucratic white papers/detailed slide decks on China’s AI scene, longform profiles of people who work in data annotation factories, the occasional rants/rebuttals that often foster regret, the rare insightful reflection, and the even rarer super dorky podcast episode, then you might as well come along for the ride. Thanks to the ones who brought us to the dance — you know who you are even though I can’t shoutout everyone personally. Let’s keep dancing and see where the night takes us.

…as always, the archive of all past issues is here and please please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay support access for all AND compensation for awesome ChinAI contributors).

Reflections - Trajectories

We’ll return to regularly scheduled programming on Taihe translations next week, but I wanted to take some time and space at the 2-year mark to throw out some ideas about this concept of “technological trajectories” from the academic literature on innovation studies/economics of technical change, and reflect on how this concept can usefully capture some trends in how “China-watchers,” China analysts, and foreign policy folks think about China and technology. Unfortunately, this is all relatively US-centric, but I’d welcome thoughts/reflections from people more plugged into other communities.

Let’s start with Giovanni Dosi’s seminal article (cited 10,000+ times per Google Scholar) on “technological trajectories,” which he defines as “the pattern of ‘normal’ problem solving activity (i.e. of ‘progress’) on the ground of a technological paradigm.” In other words, technological trajectories capture a regularity in the interaction between a broad range of economic, institutional, and social factors that characterize technological development within a particular paradigm. There are three key features to highlight about these trajectories:

Some technological developments have an internal logic of their own (e.g. solar technology may be “more decentralizing in both a technical and political sense,” whereas nuclear power is more centralizing.

But technological trajectories are not determined by technical properties alone. They are also shaped by how that technology interacts with a whole range of other actors (institutions, social forces, etc.)

Crucially, we can observe a regular pattern in those interactions.

Technological trajectories come in various forms. As Dosi notes, “There might be more general or more circumscribed as well as more powerful or less powerful ‘trajectories.’” One relatively narrow type is a performance trajectory, which maps the rate at which technological development is progressing in a particular industry. A representative example is Moore’s Law, which states that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles about every two years. Moore’s Law has become embedded in the semiconductor technology roadmap which sets the baseline assumptions for how a range of institutions, firms, and other political actors plan their development of semiconductor technology.

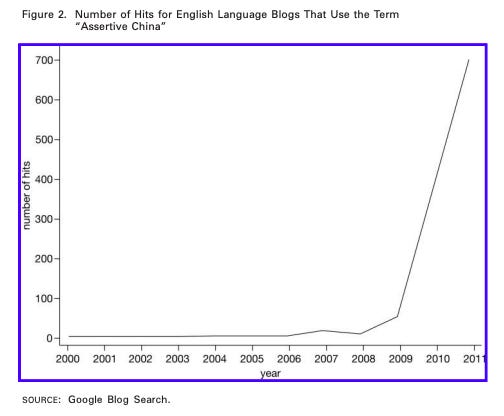

We can see analogues of performance trajectories in the “China-watching” space. The classic example is the rise of China’s “new assertiveness” meme back around the turn of the last decade (2009-2011), deconstructed in a must-read piece by Alastair Iain Johnston. The “new assertiveness” meme refers to how “it ha[d] become increasingly common in U.S. media, pundit, and academic circles to describe the diplomacy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as newly or increasingly assertive.”

Figure 2 of his piece gives a nice snapshot of this meme’s performance trajectory:

Johnston spent the bulk of the piece expertly debunking the meme, but what I’m most interested is in the parallels between this performance trajectory in “China-watching” and the performance trajectories in technological development. To that end, Johnston concludes, “the new assertiveness meme may reflect an important but understudied feature of international relations going forward—that is, the speed with which discursive bandwagoning (or herding, to use a different metaphor) in the online media and the pundit blogosphere creates faulty conventional wisdoms.” Similar to Moore’s law and the semiconductor roadmap, the “new assertiveness” meme took on a logic of its own, one that became embedded in the assumptions of those that followed the discursive bandwagoning of the online media and pundit blogosphere.

We can identify similar performance trajectories in analysis of China’s technological development. The “New Cold War” meme and “AI arms race” meme are good examples. Let’s look back on this one exchange on Twitter that is so fitting for my point that I sometimes wonder if it happened at all. In ChinAI #54, I called out how Paul Mozur, the leading China tech journalist for the New York Times, and Paul Triolo, head of geo-technology for Eurasia Group, were downright giddy about “being right” and “starting” the US-China Tech Cold War arms race meme. Without any sense of absurdity or irony, Triolo refers to Mozur as “the Wozniak” of the meme and himself as taking on “the Jobs role.” Like Jobs and Wozniak, they see themselves as the pioneers of this performance trajectory — just swap out iPhones for the “New Cold War” meme as the product they’re selling.

We can see a similar trajectory for the “AI arms race” meme. With my coauthors, I wrote in a Foreign Affairs article that before 2016 barely any articles mentioned the phrase “AI arms race,” whereas in November 2018 (when we were writing), “an article on the subject gets published virtually every week, and Googling the term yields more than 50,000 hits.” A search for that specific phrase now turns up 90,000+ hits.

I’m not going to debunk each of these memes in detail here. You can start with ChinAI #53 for my case. Rather, just like with the “new assertiveness meme,” what’s more interesting to me is how this trajectory unfolds. How do we prevent the next Moore’s Law for AI Dummies? This past year, I’ve spilled a lot of ink on rebutting specific individuals, but I think that was a flawed approach on my part if one takes this broader view of trajectories. Few individuals wake up and plan their day around how to best spread dangerous and inaccurate memes. But we all passively absorb assumptions from institutions like the New York Times and the Eurasia Group, we all crave the #clout that comes from jumping on the discursive bandwagon, and we all draw on existing concepts in the literature for our own research proposals. Eviscerating an individual’s points is a quick happiness hit; reforming institutions and adding brakes to mechanisms that facilitate discursive bandwagoning brings that abiding joy.

That was just the easy stuff — stay with me here. Let’s now turn to broader technological trajectories. There are some technological trajectories that extend beyond just the rate of development in a particular industry to larger political implications. Consider a trajectory of electric systems. The following draws heavily from Allan Dafoe’s 2015 article on Technological Determinism, which I’d suggest everyone interested in the impact of technology to read. Before World War I, British systems of producing and distributing electric power were much smaller than those in the U.S. and Germany because the British valued local control and smallness of scale. However, under the pressures of WWI, British electric systems were networked and enlarged, contrary to “prevailing British political values.” (Hughes, Networks of Power, 79). In this whole story, Allan identifies the key factor of “military–economic adaptationism—in which economic and military competition constrain sociotechnical evolution to deterministic paths.”

What, then, are the broader technological trajectories of the “China-watching space” toward China’s AI development? The “U.S.-China great power competition” trajectory is a clear candidate. The “technology” is the tendency to view everything related to China’s technological development through the lens of U.S.-China great power competition. The “military-economic adaptive pressures” are many. AI Superpowers sells better than National AI capabilities are very arbitrary and fuzzy to measure, so other countries beside the U.S. and China still have significant AI capabilities depending on the measures one chooses. There’s also this underlying desire in many of us to be part of a great challenge or fight in our lifetimes, and the prospect of a U.S.-China power transition has taken on that mantle for some. And to be clear, there is the very reality of increasing economic and military competition between the two countries.

So what do you, as an aspiring, romantically realist up-and-comer interested in China’s AI development, who has somehow stumbled upon a platform of sorts, do in the face of this trajectory? You find yourself engaged in the U.S. national security community’s campaign to “Make America Technologically Great Again (MATGA),” which doubles as a glorified dick-measuring contest in which everything is about achieving technological dominance over China. You spend a lot of time thinking about better frameworks for comparing “national AI capabilities” and challenging the notion of what it means to be more technologically dominant, but all you do is provide a better ruler, if you will. And well, you’ve already spent two years on a PhD topic that is firmly rooted in the U.S.-China great power competition trajectory. So you tell yourself that you’ll start to research the issues you really care about after you finish the dissertation — and, of course, after the follow-on projects that will spring from it.

When powerful people propose that the U.S. should not allow any Chinese international students to study science and technology, you reason back in the language of the great power trajectory — this will only undermine US competitiveness with China! — as opposed to how this is contrary to prevailing American political values. You tell yourself that your think tank has to first establish credibility by adhering to this vision of national security limited to this great power trajectory before it expands to tackling a broader vision. You tell your spouse you just need to grind a couple more years at this law firm or consultancy or investment bank before you pursue something that you really believe in. But you never do. After all, there’s a reason they’re called career trajectories.

Or maybe…just maybe, you start to change your trajectory.

ChinAI Links (Four to Forward)

Must-read: Death of a Quantum Man for The Wire China by Shen Lu

There has been so much brilliant coverage of the U.S.-China trade/tech war, and some of the coverage has captured the tensions Chinese American face caught in the middle. But I feel like something has been missing from the coverage. It's something that John Cho, a Korean American actor, talked about in a Vulture profile re: how Asian stars look so much better in their Asian films than in their American films. The reason: relative to the Asian films, Asian stars in American films were carelessly lit, whereas the white people were carefully lit. John reflects, "If you don’t think of a person as fully human, you sort of stop short and go, That’s good enough." I've been searching for a story that depicts the Chinese American experience in the midst of U.S.-China geopolitical competition in a way that sees us as "carefully lit" human beings. I think Shen Lu's piece is the best I’ve seen in terms of capturing that.

Should-Read: My three favorite translations from this past year

I chose these three, in part, because they all challenged the trajectories that shape coverage of China’s AI landscape. I want to do more of these next year:

ChinAI #77: A Strong Argument Against Facial Recognition in the Beijing Subway — Tsinghua Professor Lao Dongyan makes a strong, detailed case against the encroaching reach of facial recognition technology.

ChinAI #66: Autumn Chrysanthemums on the Bridge (poetry generated by Huawei’s AI Poet “Yuefu”): Special thank you to Ru-Ping Chen who helped with some amazing translations of classical Chinese poetry composed by Huawei’s AI Poet.

ChinAI #58: Making Knives Better & Landscape of China's Intelligent Manufacturing — On machine quality inspection in cutting tool production lines, featuring companies and voices in smart manufacturing from outside Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen; and comparisons between China and countries other than the U.S. (Germany, Switzerland, Japan).

Thank you for reading and engaging.

These are Jeff Ding's (sometimes) weekly translations of Chinese-language musings on AI and related topics. Jeff is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford and a researcher at the Center for the Governance of AI at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute.

Check out the archive of all past issues here & please subscribe here to support ChinAI under a Guardian/Wikipedia-style tipping model (everyone gets the same content but those who can pay for a subscription will support access for all).

Any suggestions or feedback? Let me know at chinainewsletter@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jjding99